Many learning design theories advocate for a more student-centered process. A whole book could be written on the various options available, but here I just want to touch on one of these: backward design.

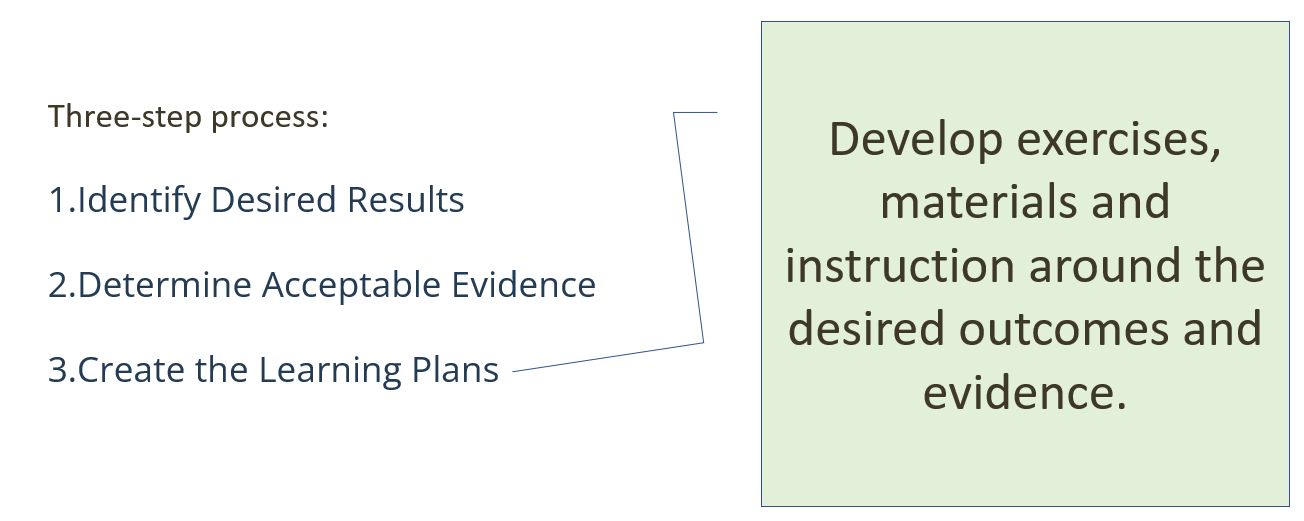

I’ve chosen backward design as at its heart it is a simple four-point process for designing learning activities or courses, which is useful to illustrate the thoughts presented in my previous essay on “Being student-centered”. Essentially, designers of learning are asked to do tasks in the following order:

Identify the desired results

Determine acceptable evidence

Create learning plans

And, in a bit more detail:

1. Identify the desired results

Articulate what learners should be able to understand and do after provided instruction. This is usually done by designing SMART and specific Learning Outcomes which not only outlines what the learner is expected to have learned by the end of a course or session, but the extent of that learning. SMART is an acronym that is often used when designing learning outcomes.

It asks us to be Specific (what precisely is to be learned – skills, knowledge, behaviours?), Measurable (how will you and the learners themselves know that the desired outcome has been achieved?), Achievable (is the learning outcome realistic and attainable for the target learners and in the time and space available?), Relevant (are the learning outcome aligned with overall goals and objectives and are they meaningful and valuable for the learners?), and Time-bound (what is the deadline for this outcome to be achieved?).

2. Determine acceptable evidence

Determine what types of assessments and measures would clarify when and whether students can perform the desired outcomes. This is not necessarily about summative assessments, but that is often one of the key indicators of success. Summative assessments are useful as they generally provide a grade upon which learners can be ranked by how successful they have met the outcome, according to a well-aligned set of criteria.

Other forms of evidence might be learner feedback, observations about their engagement and knowledge, informal discussions, or formative assessments including mini quizzes and success as carrying out activities. Make a list of the types of evidence that will determine if a learner has successfully achieved the outcome and ensure that you evidence this.

3. Create learning plans

The last element is to develop exercises, materials and instruction around the desired outcomes and evidence. This is the stuff that will help learners to learn and support you when you are teaching. Structure is important here. You need to ensure that the material is suitable both in terms of how accessible it is and in terms of ensuring that it is the right level for the learners to understand (you would approach this very differently for a 10 year old child than you would an adult, and again, you would offer materials differently for learners who are retired than those in their 20s). Similarly, that structure should consider the diversity of your learners. This might include consideration of age, gender, language, educational background, disabilities, and study/work/life balance.

Materials could be all kinds of things including readings, videos, interactive activities, discussions, collaborative work, scenarios, case studies, independent investigation, etc. The importance here, is to ensure that the materials and teaching approach fits the learners and enables them to achieve the learning outcomes (i.e. the learning plan and materials should be aligned to the learning outcomes).

Understanding by Design

Backward Design is sometimes called Understanding by Design. It was first developed in the 1990’s by two American educationists, Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins. They popularised their approach in their 1998 book Understanding by Design and have published a range of other books and articles themselves and with others to further demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

The key, really, is to turn upside down the approach that many educationists take when designing a course. It’s almost instinctive for us to start with the bit that we need to do, so traditionally the first though is ‘how am I going to teach this subject?’.

Such an approach led to the creation of learning materials and teaching plans first. McTighe and Wiggins argued that this approach could lead to confusion for learners and for them to learn things that are not really necessary to achieve success. Therefore, by starting with outcomes instead, the educationist is forced to align everything they do to those outcomes. Thus the consideration of ‘acceptable evidence’ directs the assessment and feedback strategies, while the content and lesson plans are better aligned to address the learning outcomes, rather than just speak to the general topic of study.